The Land’s Memory of Two Millenia of Rice Farming

The Land’s Memory of Two Millenia of Rice Farming

In the Yayoi period, nearly all of Japan engaged in rice farming. In northern Kumamoto Prefecture rice farming was started in the flat land of the Kikuchi River Basin, where it was easy to draw water along the river.

Later, productivity increased via the usage of iron farming tools, and the land became abundant through rice farming. This abundance has been connected to the birth of a rich and diverse 'funeral culture', with evidence such as luxurious burial items excavated from the 'Eta Funayama Burial Mound' and the 'Chibusan Burial Mound' which is decorated with pictures and other ornamentation. At last, supported by advancing technology, the curtain rose on the rice farming culture of the Kikuchi River Basin.

The Kikuchi River Basin is a region blessed with water that is clean and high in minerals, originating from the Kikuchi Gorge in Mt. Aso's outer rim. Nearly 2,000 years ago, the rice farming here was just a few tiny paddy fields at. But, with the introduction of irrigation technology came the large-scale 'Jorisei' land division system that was imposed all throughout Japan starting in the 8th century. Under this system, just 1 'division' of the Kikuchi River Basin's plains supported nearly 1ha (10,000m2) of rice paddies in Japan's antiquity.

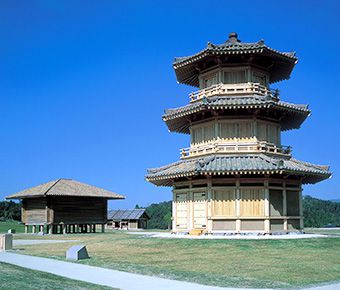

Also, thanks to this region's abundance of rice, the Yamato Imperial Court built the ancient castle 'Kikuchi Castle', where rice storage was constructed so that this area could function as a military supply base. Even as the eras changed, the jorisei land division system did not need any major changes. So, when you visit Kikuchi Castle, you will be able to see the country scenery as it has existed for over a thousand years, neatly divided up like a Go board.

After the middle ages, through improvements in farm construction technology such as reservoir creation and waterway construction, the Kikuchi River Basin was outfitted with 'ides' (irrigation ditches). These transformed the waterless elevated areas into rice paddy fields.

With further improvements to measurement and engineering in the Edo Period, long-distance 'ide' were routed through all parts of the region. The 11km 'hara-ide' (source waterway) was made by manually drilling a 454m waterway tunnel; this opened up the mountain regions where it was difficult to make paddy fields, enabling rice farming there. The 'hara-ide' has been used for over 300 years, and is still used to provide water to the region's fields today.

Bansho Tanada(Rice Terraces) are made of stone, having been built by clearing away the steep face of the mountain. However, the buildings etc. within the village are built atop masonry, built using traditional construction methods like mud walls or mortar walls. Visitors can enjoy seeing the mountain village living in harmony with the natural landscape, including rice terraces and the old rows of houses.

Since early modern times, in the coastal regions, embankment and sluice gate construction techniques have developed, and reclamation projects have continued. There are expansive tidal flats at the mouth of the Kikuchi River, and by building embankments to stop the tides, it enabled the spread of cultivated land. The scale of that land has grown larger year-by-year.

During the mid-Meiji era, the 'Old Tamana Land Reclamation Sites' embankment was constructed-- at that time, the largest-scale embankment in Japan with 3-6m tall stonework reaching a length of 5.2km. Ultimately, this resulted in the reclamation of 3,000ha of fertile land from the sea. This embankment, sometimes called the 'Seaside Great Wall of China', has walls like that of a castle; anyone viewing it from up close will be totally overwhelmed by its size-- during the harvest season, you can see a beautiful contrast between the golden ears of rice and the stonework of the masonry.

In modern times, along the marshlands of the Kikuchi River, the Kikuchi City-born agricultural engineer Tomita Jinpei poured all his personal assets into developing an underdrainage technique in order to dry out poorly irrigated fields that did not drain properly even when it was time for them to be harvested. At the same time, he also developed a method of using the water taken from these fields for times of drought, a technique that spread all throughout Japan.

The Kikuchi River not only provided water for paddy fields; it was vital for the shipping of rice as well.

In the 450 years of history following the 11th century, the Kikuchi Clan dominated Kyushu, building a fortune on rice transport via the Kikuchi River. Through their stable rule of this region, they contributed to the development of rice farming. Water transportation via the Kikuchi River gradually became more important in the Edo period. When you travel down the Kikuchi River, you'll be able to see the stone walls of the 'Takase Harbor Ruins.' Here is where the Kikuchi River Basin's annual rice tax was gathered. Then, using stone-paved slopes called a 'tawara-korogashi', bags of rice were loaded onto ships that would take the rice to Osaka or other locations.

In the Edo Era, the region became lively with trade thanks to Kikuchi River's harbor and the town of Yamagayu which intersected the "Buzen Kaido" road. Numerous shops lined the streets, dealing in rice wholesale, koji mold, sake, sweets, and more. The breweries and koji mold growers are still in business today, much to the delight of visitors who come to see the townscape.

The merchants who made their fortunes on rice and sake helped fund the 'Yachiyoza Theater' playhouse, which is still just as active today as it was when it was built. Beloved by the locals and many kabuki actors, at this playhouse you can experience the atmosphere of ancient times.

Within the Kikuchi River Basin, numerous customs and festivals dedicated to praying to gods of the fields for abundant harvests have been passed down. During 'Koshogatsu' (meaning 'Little New Year', celebrating the 15th day of the first lunar month), children chase out the moles that destroy the ridges of the fields; prior to field-planting, rain prayer dances are performed to call the rain, and in late summer the 'Fuuchinsai' (Wind-Calming Festival) is held in order to pray that the rice is not knocked over by the winds of a typhoon. After the harvest, from autumn onwards there are regular festivals to show gratitude for the crops, as well as ceremonial dances and other events in order to pray for an abundant harvest in the coming seasons.

Also, amongst the food that has been handed down in this region, there remain numerous dishes utilizing regional ingredients mixed with local rice. Among these is 'konoshiro-no-maruzushi', a dish utilizing fresh konoshiro fish caught from the Ariake Sea (which the Kikuchi River empties into) which are stuffed with sushi rice. There is also 'ganemeshi', which is made with simmered parts of river crabs caught in the Kikuchi River.

This region's traditional sake is called 'akazake', a red-colored sake which gets its red color from the ashes of burned plants that are put into it in order to preserve it. The word 'aka' means 'red' in Japanese, and this sake is true to its name. With a strong sweet flavor, during the Edo period it was treated as the representative sake of the feudal domain, and was even offered to the shogunate. It was formerly consumed at local festivals and celebrations, but at present has become a staple for New Years' celebrations.

Through the continuance of rice farming, the region developed as the central production region for 'Higomai', a type of rice known in the Edo period as the best in all of Japan. This rice was used as 'okuma' (rice dedicated to the gods) by shoguns, and it was so famous that within Osaka it commonly given to famous actors and yokozunas as a celebratory gift, with the tag 'Higomai Shinjo' (A Gift of Higomai.) As one of Japan's foremost rice locations, the Kikuchi River Basin continues to receive the highest ratings in Japan today.

In this way, through the ancient 'jori' land divisions in the plains, the medieval 'ide' and terraced fields in the mountains , the early modern land reclamations among the coasts, and the modern creations of embankments in the marshland systems, the passion and wisdom that this land's ancestors used to widen the scope of land usage to support 2,000 years of rice farming can be seen residing in this land even today. When you visit, you will be able to see all these forms together in one place, in a compact form. Additionally, you'll also be able to fully experience the intangible culture of rice farming that lives and breathes within lively festivals, plentiful food, and more.

Like a microcosm of Japan's rice farming culture from past to present, the Kikuchi River Basin is a rare place where you can encounter the cultural scenery of Japan's rice farming, as well all the entertainment and food culture that it brought.